The Paradox of ‘Nigerian Luxury Houses’

In 1843, two Nigerian port town rulers engaged in a silent architectural competition. King Eyimba of Duke Town, heard that King Jaja of Opobo had ordered for a prefabricated English wooden house and placed an order of his own: a palace made of iron. Under the sweltering heat of the Southern Nigerian sun, the allure of grandiose structures surpassed concerns of practicality. This historical rivalry, through ambitious projects, set the stage for a gradual transformation of Nigerian architecture—a transition marked by the gradual dissolution of traditional forms. From then, till now, the constant pursuit of modernity and the emulation of Western luxuries have reshaped the country’s architectural landscape, and structures have evolved to include imported designs and foreign comforts.

Luxury is a moving target, shaped by culture, social status and individual desires. This complexity is what makes Nigerian architecture so intriguing. The gradual dilution of traditional architectural forms speaks volumes about the shifting priorities within our society. While this can be sometimes misconstrued as a simple loss of identity, the reality is more nuanced. When King Eyimba and King Jaja carried out their extravagant building projects, it wasn’t (just) about aesthetics and displays of wealth, they were strategic power plays. The two kings understood that architectural grandeur symbolized power and prosperity, ultimately attracting trade and solidifying their political dominance. Fast forward to almost two centuries later, Nigeria’s architectural landscape reflects a similar drive – albeit on a grander scale. Take the most recent developments of the exclusive enclaves of Banana Island (2000) and the ambitious skyline of Eko Atlantic (2027). These high-end districts set their sights on emulating the success stories of New York’s Tribeca or Dubai.

The stakes have become much bigger than a duel between port kings as contemporary projects represent a struggle for global relevance. The aspiration is to be seen on the same stage as major international cities, a desire to attract not just trade but also investment and a meaningful place in the global conversation. This is understandable, and some might even argue, commendable. The concern, however, is not the ambition itself, but the potential cost. The relentless pursuit of a cosmopolitan aesthetic risks overlooking a crucial opportunity – to create spaces that celebrate both tradition and progress. Somewhere along the way, we seem to have lost sight of the luxuries that are peculiar to our communities and the true essence of Nigerian identity risks being completely overshadowed by imported ideals and foreign aspirations.

Traditional

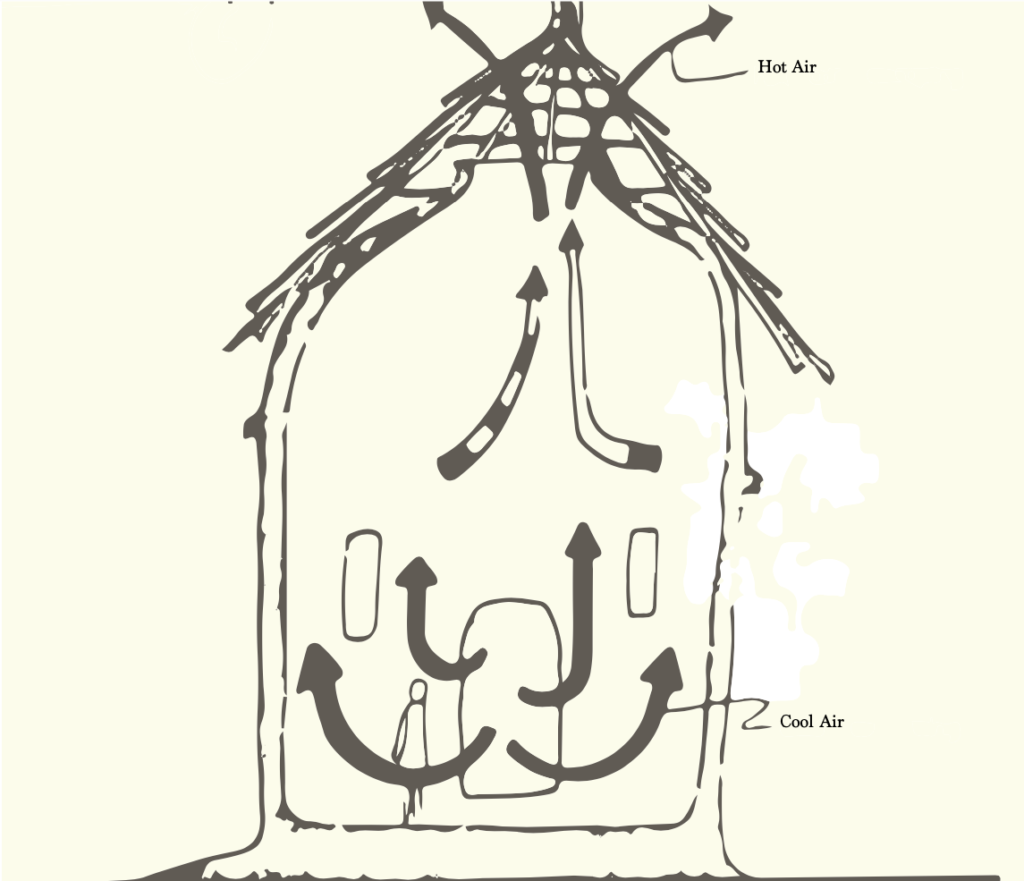

Before the arrival of colonial influences and the return of Afro-brazillians, traditional Nigerian architecture reflected the climate, culture and belief of its people. Each tribe possessed unique architectural styles that emphasized communal living. These styles, primarily compound houses, were deeply influenced by the prevalent polygamous family structures and the wise utilization of readily available materials like bamboo, palm fronds, sun dried mud bricks and thatched roofs. Similar to the Igbo and Hausa, the Yoruba people placed immense value on family and community. The central feature of their architecture was the “agbo’le,” a large open courtyard. Large open courtyards act as natural ventilation shafts, light wells, and social spaces, promoting cooler temperatures, brighter interiors, and a sense of community. Houses with thick mud walls and termite-resistant roofs surrounded the agbo’le, typically built as a continuous structure for extended families.

The Hausa people also built large housing units, encompassing a man, his wives, and children, and were further divided into sections with specific functions. Unlike Igbo and Yoruba styles, Hausa architecture embraced intricate calligraphy, surface design, and ornamental elements, particularly on palaces, showcasing their artistic prowess. Despite these unique embellishments, the core emphasis on family remained. The Igbo mirrored the focus on family with their traditional round mud houses clustered together in compounds. The “Obi,” a vital structure, served as the meeting house for the family head and his guests. Other rooms within the compound catered to the extended family, maintaining designated spaces for men, women, and children. This layout reinforced the Igbo social structure and the importance of communal living.

In pre-colonial Nigerian architecture, the concept of luxury differed significantly from our contemporary understanding. Rather than focusing solely on ostentatious displays of wealth, luxury was characterized by functionality, artistry, and social standing. Structures considered luxurious were often larger in scale and featured intricate detailing, spacious courtyards, and multiple rooms for various functions. Palaces, such as the Emir’s Palace in Zazzau, exemplified this notion of luxury, boasting impressive size, defensive features like high walls, and strategic locations that underscored a ruler’s power and authority. Luxury was evident in the skillful utilization of locally available materials, with well-crafted thatched roofs and intricate mudbrick patterns serving as testaments to the builders’ expertise. The incorporation of intricate decorations, such as Hausa calligraphy or symbolic carvings found in Igbo meeting houses, added an artistic dimension to these structures.

The 1930’s

African architecture has always incorporated some level of privacy, but the arrival of Islam in certain regions introduced a new emphasis on it. For example, the Hausa people adopted the “azure” – a space specifically designed to shield women from contact with male visitors. However, the spread of Christianity and European colonization in the 19th and early 20th centuries sparked a more dramatic shift towards privacy in Nigerian architecture. As Christianity gained traction, traditional polygamous family structures began to give way to smaller, nuclear families. This societal evolution necessitated changes in housing design. The once-dominant compound houses, with their shared courtyards, were no longer suitable.

Architects adapted these traditional structures, incorporating elements from Afro-Brazilian styles brought back by returning slaves. The central courtyard, a defining feature of the compound house, was replaced by a central indoor lobby, similar to those found in Brazilian homes. These architectural changes mirrored the broader societal shift towards privacy and the changing dynamics of family life in Nigeria.

The influx of Afro-Brazilian returnees not only brought a new architectural style, but also transformed it into a symbol of wealth and modernity among the local upper class (prosperous merchants participating in the booming capitalist cocoa and coffee export economy of the 1930’s). These multi-level “Brazilian style” houses, featuring imported materials like corrugated iron and cement, represented a stark departure from traditional Yoruba practices. Two stories became the new standard, and even though building such a house challenged the authority of traditional rulers, the new ambitious class of people did it anyway.

The flamboyant Brazilian houses, while criticized for ecological shortcomings, offered a way to be self-assured and modern, independent of colonial influence. The traditional compound houses became less common and the desire for increased privacy grew, marking a significant departure in Nigerian architectural history, traditionally reliant on readily available, local materials like mud brick and timber. The environmental impact of these choices sparked a debate that continues today, raising questions about balancing modernity with ecological responsibility.

Credit: victorlepik.com

1960’s

In the 1960s, following Nigeria’s independence from Britain and the broader wave of decolonization across Sub-Saharan Africa, architecture became a vital tool for expressing national identity. This period witnessed a surge in construction in Africa, with new parliament buildings, central banks, stadia, and other monumental structures being erected. Modern and futuristic designs symbolized the aspirations of newly independent nations, reflecting a forward-looking spirit buoyed by economic prosperity and optimism.

The euphoria of independence fueled a desire for architecture that mirrored the nation’s aspirations. Yet, this architectural renaissance also revealed the complexities and contradictions inherent in the independence process. Many of these grand projects were designed by foreign architects, raising questions about the authenticity of the national identity being projected. Did these structures embody a genuine desire for modernity and cosmopolitanism? Or were they mere vanity projects, masking the self-serving agendas of authoritarian regimes? Did they, in any way, reflect the aspirations of the nation’s architects, or the people themselves?

As the initial euphoria of independence settled, a critical reevaluation began. The disconnect between imported styles and local needs became evident. Architects, educated both locally and abroad, started a movement to “decolonize” African architecture. They sought to integrate indigenous practices, materials, and climate considerations into their designs. Projects done by Demas Nwoko and Francis Kere showcase this approach, where modern needs are met through traditional construction methods and community involvement.

In these times, luxury was associated with size, employing imported materials like glass, steel and concrete to showcase a modern and cosmopolitan lifestyle. As the desire for a distinct national identity grew, luxury houses began to incorporate elements and craftsmanship, they didn’t entirely abandon traditional layouts, courtyard concepts were usually reinterpreted into more private internal spaces, offering a modern twist on a familiar theme.

Demas Nwoko New Culture Studio, Ibadan. Credit: Folu Oyefeso

1990’s

In post-colonial Nigeria, the 1980s and 1990s was a time where modern aspirations intertwined with a deep appreciation for Nigerian heritage, creating a unique architectural style. Luxury homes in this era embraced both privacy and a connection to nature. Global influences were present, but much more subtly than they are now. Luxury finishes and imported fixtures were used sparingly, adding a touch of international flair without overshadowing Nigerian identity. Intricate woodwork, decorative details, and hand-woven textiles added a layer of cultural richness. Modern amenities like air conditioning and well-equipped kitchens became essential, but they were cleverly integrated into the overall design to ensure a cohesive aesthetic.

Opulence in this era had a distinctly Nigerian touch. Modernist houses became the new status symbol for the upper class, while the once-luxurious “Face-Me-I-Face-You” houses became more affordable and catered to a different demographic. Lush gardens, verandas, and gazebos became staples of luxury houses. These elements not only enhanced the aesthetics but also provided tranquil spaces for relaxation, reflecting the Nigerian appreciation for nature. Some famous luxury houses incorporated traditional elements like courtyards with fountains, creating a sense of oasis within the home, often featuring artwork or paintings that celebrated Yoruba culture.

While some houses showcased imported materials like marble and tiles, the best examples balanced these with local elements, creating a unique blend of international sophistication and Nigerian heritage. Banana Island, a haven for the wealthy in Nigeria, exemplifies this architectural evolution. The older houses boast a more traditional British style with sprawling gardens, while newer ones embrace modern aesthetics, featuring clean lines and smaller footprints due to limited land.

Late 2010’s till now

Nigeria’s current luxury housing market offers a fascinating glimpse into the country’s evolving desires. Today’s luxury homes are all about cutting-edge technology and opulent interiors. Customization is king, with a growing demand for “smart homes” boasting high-tech features. Places like Banana Island even offer advanced infrastructure unavailable elsewhere in the country. This focus on the latest technology reflects a shift in priorities. Globalization and changing lifestyles have diluted the Afro-Brazilian influence that once dominated luxury architecture in favor of a more Americanised aesthetic. The Nigerian upper class, increasingly drawn to urban centers, prioritizes these modern features.

A surprising trend emerges when we look beyond high-tech interiors, though. Luxury houses often lack greenery. YouTube and Tiktok videos by popular channels like “Ola of Lagos” showcase this trend; lavish spaces with minimal to no gardens or trees, often imported interiors, devoid of connection to the natural world. These houses, even in villages, stand in stark contrast to their environment, resembling concrete jungles despite being situated in a country rich in natural beauty. Shouldn’t true luxury, especially in a polluted city, include the ability to step outside and feel fresh air amidst a well-tended garden or a terrace adorned with trees? While older, established wealth may have embraced this connection to nature, modern Nigerian architecture seems to be prioritizing imported aesthetics over the simple pleasure of integrating with the environment.

Perhaps there’s a lesson to be learned from “old money” houses, which often prioritized these elements. The rise of Eko Atlantic, a luxurious high-rise community on reclaimed land, has further impacted the landscape. While it offers stunning water views and modern amenities, its construction restricts the type of homes that can be built, limiting green spaces. As apartment complexes and penthouses become more and more popular, priorities shift, and it seems that luxury homeowners are so fixated on the “inside” that the “outside” is forgotten. Luxury destinations like Kenya and Bali offer a unique experience by blurring the lines between luxury and nature. While strides have been made in decolonizing Nigerian luxury, there remains a notable absence of reverence for biodiversity. Rather than completely replicating luxury as dictated by the west, the true essence of Nigerian luxury could rest in its ability to embrace both comfort and nature, forging a symbiotic relationship between indulgence and environmental consciousness.

Conclusion

Nigerian luxury housing has danced between functionality, colonial defiance, national identity, and a current disconnect from its verdant roots. This architectural odyssey reflects a nation in constant conversation with itself and the world. While the allure of global styles is undeniable, true luxury is achieved through synthesis. There is no doubt that contemporary Nigerian homes can recapture the wisdom of their ancestors while also seamlessly integrating nature’s bounty with cutting-edge technology. The answer lies not just in the materials used or the features installed, but in a conscious effort to create spaces that are not only luxurious, but also deeply Nigerian – sanctuaries that embrace both progress and heritage, offering respite not just from the urban heat, but also from the homogenizing forces of globalization.